African Exits Lie Beyond the Mediterranean

African startups can achieve global IPOs by shunning the U.S markets and instead looking beyond the Mediterranean to European public markets

Derin and Osarumen wrote an excellent post on the absence of exits in African tech despite billions of private capital in investment. In it, they suggest that global IPOs are beyond the reach of African startups. I don’t agree. African startups can achieve global IPOs by looking beyond the Mediterranean to European markets and not to the U.S. This piece is a rejoinder to their position and makes a case for European (small-cap) IPOs by African venture-backed companies.

The premise in their piece is that less than 20 African startups with revenue around $150m are the only ones potentially eligible for a global IPO. This position is based on a contemporary Americentric view of venture and disregards the history of venture exits in the U.S. itself, where companies traditionally listed with much less revenue than is obtainable today. African companies with significantly less revenue than $150m can retreat to that traditional path and undertake a global IPO outside of the U.S., in Europe. In fact, Mdundo, a Kenyan-based alternative to Spotify, has already set the precedent.

An unlikely African IPO

Mdundo underwent a global IPO in a European market, Nasdaq First North Denmark, in 2020. Founded in Kenya in 2014 by a Dane, the startup had rapidly grown to 5 million users within 6 years. They were part of the portfolio of one of the first angel funds and accelerators on the continent, 88mph, founded by another Dane, Kresten Buch. They raised an estimated $700,000 from 43 Danish angels via the accelerator. By the time of its IPO, it had a cumulative all-time revenue of less than $1 million. In fact, their annual revenue was a humongous, wait for it, $53,363 with losses of $131,864 in the year of the IPO. They were nonetheless successful at raising $6.4m in an oversubscribed offering on a valuation around $9m. Four years since going public, the company has grown its revenue by 30x and continues to trade on the exchange. The investors who backed them early had at least a 1,000% return on their capital invested based on the IPO price of $1.60 per share. Mdundo demonstrates that it is possible for an African startup to do a global IPO in Europe and provide an exit to investors, even on small revenues.

Public Markets as a source of Growth capital

Going public later with an expectation of >$150m revenue is a post-dotcom crash phenomenon. Pre-crash, the median time to IPO by U.S venture-backed companies was 6.8 years. Median revenue at IPO was $33 million, and only 37% of companies were profitable. Following the crash, median IPO time increased to 10.3 years, and median sales at IPO had more than tripled to $117 million. The number of IPOs had also shrunk significantly by threefold [1].

This dramatic change came about following the enactment of more stringent regulations for public companies in the wake of the Enron and Worldcom scandals. Concurrently, private capital markets expanded and became more sophisticated. This meant companies now had access to larger later-stage rounds to stay private for longer with the added benefit of delaying onerous public reporting requirements.

Africa, in comparison, doesn’t have similar depths in later-stage private capital, and neither did the U.S. in the early days of its own venture industry. In 1978, U.S. VC’s first major fundraising year, they raised $750 million, the equivalent of $3.6 billion today when adjusted for inflation. An amount that’s similar to the $3.3 billion median value of venture funding raised from 2019 to 2022 in Africa. By this metric, Africa’s venture industry is similar in magnitude to what its U.S. counterpart was in the 80s. If the metric used is VC funding per GDP, then the early to mid-90s in the U.S. would be the equivalent in Africa. This essentially bookends the comparable period of Africa’s current venture experience to the 80s and 90s in the U.S. A Harvard working paper describes that time in a way that’s relatable to today’s African venture industry. It highlights that (U.S.) venture funds of the 80s were relatively small. Fast-growing companies burnt through capital quickly while finding it difficult to attract follow-on capital to drive growth. Venture-backed companies in the U.S. in the 80s were thus constrained to approach capital markets for growth capital early on in their journey.

Just as it did then in the U.S., public markets can offer an alternative source of relatively early financing for African startups today. The London Stock Exchange (LSE) captures this well in a graphic on their website of the role public markets can play in startup financing.

AIM, the alternative investment market of the London Stock Exchange (LSE), is a market for small and growing companies. It positions itself as a competitor to venture capital for Series A to C deals. These A to C stages are where capital is increasingly constricted in Africa.

American hurdles, European bridges

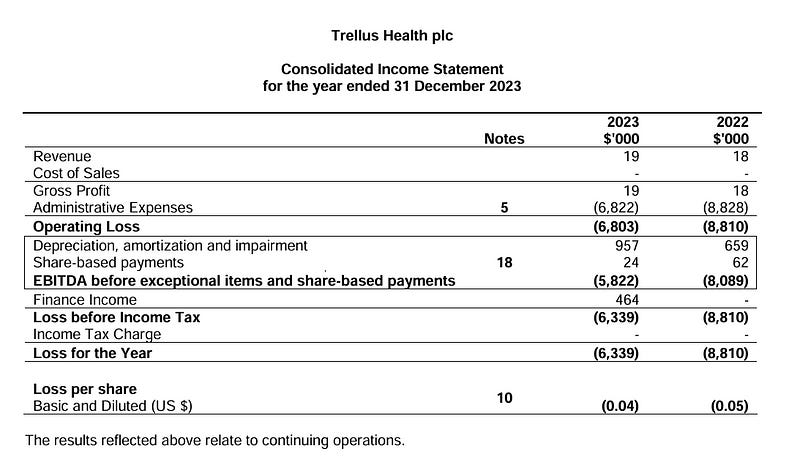

When faced with later-stage private capital constriction in their early days, successful big tech companies of today from older eras like Amazon, Google, and Apple all listed within 6 years of their founding. Amazon, for instance, listed within an incredible 3 years with <$20 million in revenue and $5 million in losses. Today, however, things are different in the U.S. Revenue <$150m is seen as subscale, and stricter regulation is pushing companies to remain private. Stripe, for instance, is a 14-year-old company with a $50 billion private valuation without an IPO in sight [2]. European markets, on the other hand, are extending bridges to encourage listing by smaller companies. Some U.S. startups are beginning to favour them over traditional American options, the NYSE and NASDAQ. An example is Trellus Health, an American digital health company that provides chronic disease management solutions. Likely fearing stringent U.S. regulations where directors now risk jail for company misadventures, they opted for an LSE AIM listing. Their financials for 2023 reveal meagre revenue of $19,000 with losses of $6.3 million (yes, you read that right).

Trellus Health demonstrates once more that small revenues and losses are not a barrier to a European IPO.

The small-cap European opportunity

Africa’s venture and indeed its public capital markets are still early and immature. Opting for welcoming European public markets as a source of capital early on in a company’s evolution seems a viable option. The exchanges themselves are keen to build pipelines and compete with VCs for high-growth deals. From their perspective, why miss out on over a decade of value accretion in a company like Stripe (arguably originally European, by the way) with a massive $50 billion valuation? Better to fund them along the way and keep all the benefits on the exchange for all that time.

Small-cap European markets enable companies to list early, grow sustainably, and raise follow-on financing. As companies grow, they can graduate into the market’s main boards. Euronext, the leading European exchange with a presence in Amsterdam, Lisbon, and Milan, provides a straightforward path to listing. Their access market has lenient listing and simplified ongoing reporting requirements.

Furthermore, average market cap and deal sizes at IPO are much less compared to Nasdaq or the NYSE. With average market caps of €60m at IPO on its access market, €102m on its growth market and €2bn on its main board. Blitzscalers, referenced in the Derin and Osarumen article, that would be small fish in U.S. markets would likely fit in well in any one of these markets. Even smaller startups, struggling to raise a Series A or B despite decent revenue and growth, have a decent chance of a successful initial public offering (IPO). Remember, Mdundo did it. Worthy to note here that going public doesn’t preclude a future acquisition; if anything, it paradoxically enhances the odds. Spotify, for instance, is arguably more likely to be aware of, trust, and acquire a public Mdundo than a private one.

African companies that opt to wait for a significant splash in a U.S. market listing should learn from the two most recent African forays, Swvl and Jumia. The former lost 97% of its value since listing on Nasdaq via a merger with a SPAC. The latter has faced significant challenges in the market, losing 25% of its share price in 5 years.

There’s an argument to be made for the counterfactual of these two African startups listing early in a small-cap European market and gaining the discipline of operating as a public company to grow sustainably and efficiently. Accruing value along the way and returning more value to its shareholders.

Proceed but with caution

The case for listing in a European (small-cap) market seems more alluring than an improbable big American market splash. It’s certainly more so than the African alternatives, such as the NGX, JSE, or Egyptian exchange. These 3 biggest exchanges on the continent don’t compare in depth or liquidity. European markets are better resourced than all of them combined and dwarf all the available later-stage private capital on the continent. Naspers, the most valuable African internet company, moved its consumer assets from the JSE to Euronext Amsterdam to access this deeper capital pool. Undergoing a European IPO process would expose African companies to thousands of global institutional investors and asset managers, many of whom are from the U.S. anyway.

Many of these investors have specific ESG and increasingly impact mandates that African companies can potentially help them fulfil. However, small-cap (European) markets are not without risks. Since 1995, European exchanges have launched eleven second-tier markets dedicated to particular categories of firms. Of these, only five still exist, many of which can suffer from limited liquidity. In Germany, the Neuer Markt was a small-cap market targeted at young and innovative firms back in the 90s. The market was popular until it collapsed due to widespread fraud in the listed companies. Wirecard, the largest financial fraud in the German DAX market, got its start in the Neuer Markt. Small-cap markets can and do fail. The exuberance of the dot-com years hopefully left some lessons in the form of better rules and management to forestall future failures.

While the impact of small-cap IPOs on African venture-backed companies is yet to be seen, Mdundo is the singular data point; the American venture history suggests that more companies should consider attempting IPOs on small-cap markets to secure additional financing and establish themselves for long-term sustainability. European markets can provide a better fit and are more accessible than American markets for relatively lower-revenue and generally less mature African companies. These markets have also proved resilient in previous crashes and are increasingly a destination for global tech IPOs. European markets are ideally placed to provide the exit opportunity and growth capital financing that African venture-backed companies sorely need. To answer the question in the article that prompted this piece, “When will the exits cross the road?”. Well, the road is a sea, and the exits are possible today; companies just need to look beyond the Mediterranean.

— —

Thanks to Ayobami, Big Chief Asemota and Victoria for reading drafts of this and providing valuable feedback.

Notes

My own analysis based on data from “Initial Public Offerings: Updated Statistics by Jay R. Ritter

In today's increasingly deep private venture world, Stripe doesn’t necessarily have to IPO; they could remain private indefinitely and still be successful. Germany’s second biggest fintech is towing that private path. IPOs are not the be all and end all of venture. The odds are however high that an IPO will eventually materialize.